Tax Practitioners Board exposure draft

The Tax Practitioners Board (TPB) has released this draft Information Sheet (TPB(I) D55/2024) as an exposure draft and invites comments and submissions in relation to the information contained in it. The closing date for submissions was previously 24 September 2024, this date has now been extended with a new closing date to be advised. The TPB will then consider any submissions before settling its position, undertaking any further consultation required and finalising the TPB(I).

Written submissions should be made via email at tpbsubmissions@tpb.gov.au or by mail to:

Tax Practitioners Board

GPO Box 1620

SYDNEY NSW 2001

Disclaimer

This document is in draft form, and when finalised, will be intended as information only. It provides information regarding the TPB’s position on the application of sections 20 and 25 of the Tax Agent Services (Code of Professional Conduct) Determination 2024 (the Determination).

While this draft TPB(I) seeks to provide practical assistance and explanation, it does not exhaust, prescribe or limit the scope of the TPB’s powers in the Tax Agent Services Act 2009 (TASA). In addition, please note that the principles, explanations and examples in this draft TPB(I) do not constitute legal advice and do not create additional rights or legal obligations beyond those that are contained in the TASA or which may exist at law. Please refer to the TASA and the Determination for the precise content of the legislative requirements.

Document history

This draft TPB(I) was issued on 6 August 2024 and is based on the TASA as at the date of issue.

Issued: 6 August 2024

Introduction

- This draft Information sheet (draft TPB(I)) has been prepared by the Tax Practitioners Board (TPB)[1] to assist registered tax and BAS agents (collectively referred to as ‘registered tax practitioners’) to understand their obligations under the following:

- While the focus of this draft TPB(I) is on the obligations in sections 20 and 25 of the Determination, it is also important to note that there are also 17 obligations in the Code of Professional Conduct (Code),[4] additional obligations in the Determination, and further requirements that registered tax practitioners must comply with under the TASA. These include ongoing requirements in relation to maintaining registration under the TASA, including that a registered tax practitioner is a ‘fit and proper’ person[5]. Further, the obligations in this draft TPB(I) are in addition to obligations 5 and 6 of the Code (which relate to managing conflicts of interest and maintaining confidentiality).

- The obligations seek to outline the high professional and ethical standards expected by the community of individual tax practitioners, with the objective of:

- improving transparency and accountability

- giving the public greater confidence and trust in the integrity of the tax profession

- strengthening the regulatory framework and the regulation of the tax profession.

- In addition to the draft guidance on the obligations in sections 20 and 25 of the Determination, this draft TPB(I) also contains a number of consultation questions at paragraph 132, which may assist you in providing feedback. The TPB welcomes submissions in response to the consultation questions, and any other aspect of this draft TPB(I).

- In this TPB(I), you will find the following information:

- Background to the legislative requirements (paragraphs 6 to 11)

- Details of the obligation under section 20 (paragraphs 12 to 64)

- Details of the obligation under section 25 (paragraphs 65 to 110)

- Consequences for failing to comply with the obligations under sections 20 and 25 (paragraphs 111 to 118)

- Comparison with the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) for tax agents with a tax (financial) advice services condition (paragraphs 119 to 128)

- Case studies (paragraph 129 and 130)

- Further information (paragraph 131)

- Consultation questions (paragraph 132).

Background

- Section 30-10 of the TASA contains the Code, comprising of 17 obligations which regulate the personal and professional conduct of registered tax practitioners.

- One of these obligations is contained in subsection 30-10(17) of the TASA, which requires registered tax practitioners to comply with any obligations that the Minister determines, by legislative instrument, under section 30-12 of the TASA.

- The Australian Government recognises the vital role that registered tax practitioners play in the tax system. The government has determined that enhancement to the TASA legislative framework is required to ensure the TPB can uphold the appropriate standards of professional and ethical conduct in the profession.

- Accordingly, on 1 July 2024, the Minister determined 8 additional Code obligations, set out in the Determination, under section 30-10 of the TASA. These additional Code obligations commenced on 1 August 2024. However, the Minister has announced that the government will introduce a transitional rule that will provide registered tax practitioners until the following date to bring themselves into compliance with these new obligations:

- 1 January 2025 - for registered tax practitioners with more than 100 employees

- 1 July 2025 - for registered tax practitioners with 100 or less employees.

- The transitional rule will apply so long as registered tax practitioners continue to take genuine steps towards compliance during this period.

- This draft TPB(I) deals with 2 of these additional Code obligations set out in the Determination which relate to independence and confidentiality. More specifically, these obligations concern the management of conflicts of interest and maintaining confidentiality in dealings with Australian government agencies in a tax practitioner’s professional capacity.

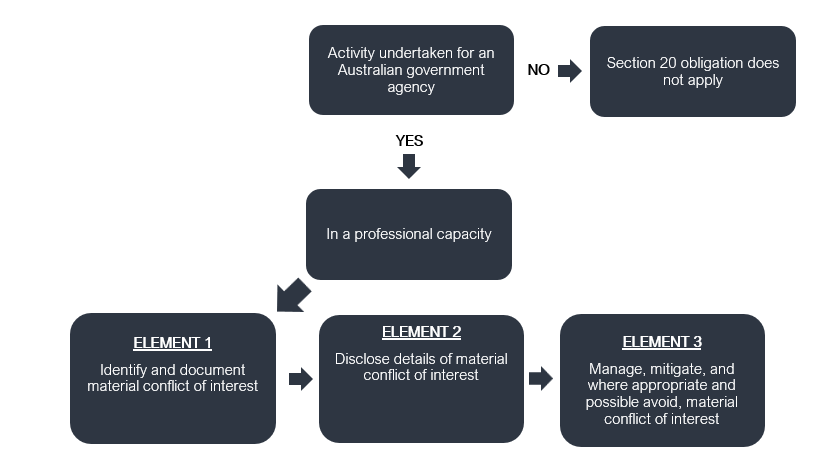

What is the obligation under section 20?

- Section 20 of the Determination requires registered tax practitioners, in relation to any activities they undertake for an Australian government agency in a professional capacity, to:

- take reasonable steps to identify and document any material conflict of interest (real or apparent) in connection with an activity undertaken for the agency

- disclose the details of any material conflict of interest (real or apparent) that arises in connection with an activity undertaken for the agency to the agency as soon as the registered tax practitioner becomes aware of the conflict

- take reasonable steps to manage, mitigate, and where appropriate and possible avoid, any material conflict of interest (real or apparent) that arises in connection with an activity undertaken for the agency (except to the extent that the agency has expressly agreed otherwise).[6]

- The obligation is intended to assist in minimising potential adverse impacts to Australian government agencies where a tax practitioner has a conflict of interest in connection with an activity undertaken for an Australian government agency. This in turn helps to achieve the objectives outlined at paragraph 3 above.

- Section 20 does not prohibit registered tax practitioners from having conflicts of interest. Rather, it creates an obligation on tax practitioners to appropriately manage and mitigate conflicts of interest that arise, or may arise, in relation to activities that they undertake for an Australian government agency in their professional capacity. Where possible and appropriate, reasonable steps must be taken to avoid conflicts unless the Australian government agency has expressly agreed to accept a particular conflict in specific circumstances.

- In addition, section 20 creates a positive obligation on registered tax practitioners to disclose the details of the conflict to the government agency as soon as the tax practitioner becomes aware of the conflict.

- In circumstances where a registered tax practitioner identifies and discloses a material conflict of interest to an Australian government agency, the continued engagement by the agency of the tax practitioner will be at the discretion of the agency having regard to the nature of the conflict and any steps taken by the practitioner to manage or mitigate the conflict. This recognises that Australian government agencies should be able to engage appropriate expertise who act independently and with integrity in undertaking activities to assist government in shaping the Australian taxation and superannuation system.

- It is also noted that the Accounting Professional and Ethical Standards Board (APESB) has released APES 110 Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants (APES 110) and APES 220 Taxation Services (APES 220), which apply to members of relevant professional bodies that have adopted it. While not binding on all registered tax practitioners, these standards provide useful guidance on what steps a registered tax practitioner can take to ensure they have adequate arrangements in place for the management of conflicts of interest that may arise in relation to activities that are undertaken in the capacity as a registered tax practitioner. APES 110 notes, among other things, that a member is required to not allow conflict of interests to override professional or business judgments,[7] while APES 220 Taxation Services also outlines requirements as to objectivity.

Activities undertaken for an Australian government agency in tax practitioner’s professional capacity

- The obligation under section 20 of the Determination applies to activities undertaken by a registered tax practitioner for an Australian government agency in the tax practitioner’s professional capacity, whether paid or otherwise.

- ‘Australian government agency’ is defined in section 995-1 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 as the Commonwealth, a State or a Territory, or an authority of the Commonwealth, or of a State or a Territory. Examples include the Department of the Treasury, Tax Practitioners Board, Australian Taxation Office, Australian Securities and Investments Commission, Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, Department of Education and Training Victoria, and NSW Health.

- Broadly, the term ‘professional capacity’ would include activities undertaken by the registered tax practitioner:

- Practically speaking, this includes providing any advice, assistance, or feedback to the government, whether paid or otherwise. However, it does not extend to activities or interactions that are of a personal nature.[10]

- Expanding the obligation to activities outside of those undertaken in an entity’s capacity as a registered tax practitioner highlights the importance of the registered tax practitioner’s role in representing the tax profession and gives the public greater confidence and assurance in the integrity of the profession.[11]

- Relevant activities that a registered tax practitioner may undertake in their professional capacity may include, but are not limited to, the following:

- providing expert advice, assistance, or feedback on technical and professional matters, including potential legislative changes

- providing advice, assistance, or feedback on strategy

- providing accounting and/or information technology (IT) services

- undertaking research activities, such as attitudinal surveys and feasibility studies

- overseeing government functions.

- The TPB is of the view that these activities may be undertaken through either a formal engagement (such as through a procurement process, or a confidential consultation process) or an informal engagement (which may include internal meetings and discussions, or informal consultation processes).

What is a ‘conflict of interest’?

- A conflict of interest is where a registered tax practitioner has a personal interest or has a duty to another person which is in conflict with the duty owed to the Australian government agency.

- A conflict of interest may be direct or indirect, and real or apparent (or perceived). Also, it can arise before the registered tax practitioner accepts an engagement or at any time during the engagement.

- A real conflict of interest arises where a registered tax practitioner has multiple competing interests and cannot objectively and impartially act in one of the interests.

- An apparent conflict of interest arises where a registered tax practitioner has multiple interests, and the nature of those interests are such that they give rise to a reasonable perception by the public that one interest could possibly impact the motivation to act for another interest. Put another way, an apparent conflict of interest arises if a fair-minded lay observer might reasonably apprehend that the tax practitioner might not bring an impartial mind to the activities they are engaged to undertake for the Australian government agency.[12]

When is a conflict of interest ‘material’?

- The TASA and TASR do not provide any guidance on when a conflict of interest will be ‘material’. Similarly, the Determination does not define the term ‘material’ in the context of conflicts of interest. However, it does provide some guidance by way of examples that distinguish between a conflict that is ‘material’ and one that is not material.[13]

- The Macquarie Dictionary[14] relevantly defines ‘material’ in the following way:

- adjective: of substantial import or much consequence

- phrase: material to, pertinent or essential to.

- The TPB considers that the test of whether a conflict of interest is ‘material’ will depend on the facts and circumstances and whether a reasonable person, having the knowledge, skill and experience of a registered tax practitioner, would expect it to be of substantial import, effect or consequence to the other entity.

- This requires the registered tax practitioner to exercise their professional judgement, taking into account the facts and circumstances surrounding the activities they are undertaking for the government agency, including:

- the information known to the tax practitioner about the activities

- the consequences for the government agency if the tax practitioner’s personal interest is such that it could give rise to a real or apparent conflict of interest that could affect their ability to discharge their duties and/or obligations to the government agency.

- A material conflict of interest may arise in circumstances that include, but are not limited to – where a registered tax practitioner:

- is engaged by a government agency to consult on proposed government law reform that impacts clients of the registered tax practitioner such that it may result in a potential or perceived benefit or gain to the registered tax practitioner and/or their clients

- may benefit or gain financially from their engagement with the government agency directly or indirectly (this could include a benefit to the registered tax practitioner themself, their employer, client and/or other associate)

- misuses confidential information obtained in dealings with government in circumstances where this conduct may result in a potential or perceived benefit or gain to the registered tax practitioner

- interferes in government decision making in circumstances where this conduct may result in a potential or perceived benefit or gain to the registered tax practitioner.

What are ‘reasonable steps to identify and document any material conflict of interest’?

- The first element of the obligation under section 20 of the Determination requires that a registered tax practitioner take reasonable steps to identify and document any material conflict of interest (whether real or apparent) in connection with an activity undertaken for the Australian government agency in the registered tax practitioner’s professional capacity. This requires the registered tax practitioner to actively turn their to mind to whether a conflict of interest exists.

- Registered tax practitioners should keep adequate records of any material conflict of interest identified in connection with an activity undertaken for an Australian government agency.

- The TASA and the Determination do not provide guidance on the specific steps that a registered tax practitioner should take to document a material conflict of interest.

- In these circumstances, the TPB expects that registered tax practitioners record the conflict of interest as soon as possible and practicable after the conflict of interest is identified. The record should contain sufficient details of the conflict of interest, including details of the materiality of the conflict.[15] For more information on the details that a practitioner should record or document, see paragraph 44 below.

- A determination of whether the registered tax practitioner has taken reasonable steps to identify and document a material conflict of interest will be a question of fact having regard to the particular circumstances of the matter in question.[16]

- Relevant factors in making a determination as to whether a practitioner has taken reasonable steps to identify and document any material conflict of interest may include the following:

- the size of the tax practitioner entity

- the type of work undertaken by the tax practitioner

- the client base of the tax practitioner

- the likelihood of conflicts of interest arising

- the sensitive nature of the activities undertaken for the government agency

- any possible adverse consequences for the government agency should a conflict of interest arise

- whether the tax practitioner has provided training to staff on identifying, disclosing and documenting conflicts of interest

- whether the tax practitioner has established procedures for the disclosure and record-keeping of potential conflicts of interest

- whether the tax practitioner has established procedures for identifying and documenting conflicts of interest, which could include:

- preliminary conflict checks prior to accepting clients or allocating staff to projects

- maintaining, and periodically reviewing, a conflict of interest register

- information handling procedures that utilise technology to limit information access to those with a legitimate need to know.

Disclose details of any material conflict of interest as soon as you become aware of the conflict

- The second element of the obligation under section 20 of the Determination requires that a registered tax practitioner disclose the details of any material conflict of interest (real or apparent) that arises in connection with an activity undertaken for the agency to the agency as soon as the tax practitioner becomes aware of the conflict.

- The obligation to disclose a conflict of interest is not limited to a registered tax practitioner disclosing information about their own material conflicts of interest. It extends to any material conflict of interest that they are aware of that arises in connection with any activity undertaken for the agency (whether the same or different activity) or in relation to any activity undertaken for another government agency. This may include any conflict of interest of any employee, associate, contractor or other relevant entity.

- For example, where a tax practitioner is undertaking an activity for an agency in their professional capacity and knows of another person’s or entity’s conflict of interest in undertaking the same or a different activity for that agency, section 20 of the Determination imposes an obligation on the registered tax practitioner to disclose the details of that conflict of interest to the agency.

- The material conflict of interest must be disclosed as soon as the registered tax practitioner becomes aware of the conflict.

What details need to be disclosed to the agency

- Details to disclose to the government agency may include, but are not limited to, the following:

- the nature of the conflict

- the extent of the conflict

- what interest, association or incentive gives rise to the conflict

- the identity of the registered tax practitioners or others related to the conflict and the extent to which they have been involved in the services provided to the government agency

- when the conflict was first identified

- how the advice or services provided to the government agency might have been different had there not been a conflict of interest

- any benefit, financial or otherwise, obtained due to the conflict of interest

- whether any actions have been taken or are proposed to avoid the conflict or to mitigate any damage arising from the conflict.

- The disclosure should:

- be made as soon as the registered tax practitioner becomes aware of the material conflict of interest

- be specific and meaningful to the Australian government agency

- refer to the specific activities to which the conflict relates, and

- allow the government agency a reasonable time to assess the effect of the conflict of interest.

- The form of the disclosure must be sufficient to allow the government agency to make an informed decision about how the conflict may affect the activities the registered tax practitioner is engaged in and the management of those activities. The government agency will then determine whether, and to what extent, the registered tax practitioner can continue to engage in those activities.

- Where a registered tax practitioner is unsure as to whether a conflict of interest arises or whether the conflict is material or not, the tax practitioner should err on the side of caution and disclose the details of the potential conflict of interest to the relevant government agency.

What are ‘reasonable steps to manage, mitigate, and where appropriate and possible avoid, any material conflict of interest’?

- The third element of the obligation under section 20 of the Determination requires a registered tax practitioner to take reasonable steps to manage, mitigate, and where appropriate and possible avoid, any material conflict of interest that arises in connection with an activity undertaken for an Australian government agency (except to the extent that the agency has expressly agreed otherwise).

- A determination of whether the conflict management arrangements employed by a registered tax practitioner are sufficiently adequate to meet the obligation under section 20 of the Determination will be a question of fact having regard to the particular circumstances.

- A number of mechanisms could be used to manage, mitigate, and avoid a conflict of interest. It will be up to the registered tax practitioner to exercise their professional judgement to determine the most appropriate method to meet the obligation under section 20 of the Determination.

Managing and mitigating a conflict of interest

- Section 20 of the Determination requires registered tax practitioners to take reasonable steps to manage and mitigate any material conflict of interest that they have identified in connection with an activity undertaken for an Australian government agency in their professional capacity.

- The Macquarie Dictionary relevantly defines ‘manage’ in the following way:

- to take charge or care of;

- to handle, direct, govern, or control in action or use.

- Further, the Macquarie Dictionary relevantly defines ‘mitigate’ in the following way:

- to moderate the severity of.

- Reasonable steps to manage and mitigate a conflict of interest may require a registered tax practitioner to:

- assess and evaluate the conflict of interest

- implement appropriate mechanisms to manage or control the impact of the conflict of interest on the tax practitioner’s advice or decisions, or the decisions of the government agency

- implement appropriate mechanisms to mitigate the conflict of interest.

- What is reasonable in the circumstances will be a case-by-case decision involving consideration of a number of factors, including:

- the size of the tax practitioner entity

- the type of work undertaken by the registered tax practitioner

- the likelihood of conflicts of interest arising.

- Examples of reasonable steps include, but are not limited to, the following:

- enforcing procedures for managing, mitigating, and avoiding conflicts of interest

- allocating staff to projects in a way that manages or avoids potential conflicts of interest, for example:

- by not allocating staff with conflicts to certain projects or tasks, or

- by allocating staff with conflicts of interest to work on initial identification and analysis of issues but having staff without conflicts of interest reviewing that analysis and making final decisions

- having internal governance policies in relation to conflicts of interest that include consequences for failing to comply with those procedures

- maintaining a conflict of interest register and information handling procedures that utilise technology to limit information access to those with a legitimate need to know.

- Additional techniques that may assist a registered tax practitioner to manage and mitigate conflicts of interest may include:

- placing a positive onus on employees or anyone else providing relevant services on behalf of the registered tax practitioner in relation to the activities undertaken for the Australian government agency to declare conflicts of interest, including reporting to appropriate people, and signing relevant declarations as appropriate

- developing a register of private interests (in conjunction with appropriate protocols) and regularly revising the register

- reviewing conflict of interest declarations periodically

- relevant training, including to employees or anyone else providing relevant services on behalf of the registered tax practitioner in relation to the activities undertaken for the Australian government agency, to ensure appropriate awareness and understanding of what constitutes a conflict of interest and how to act in accordance with relevant internal procedures and protocols (including, for example escalation procedures)

- seeking advice from an independent third party, which may include legal advice.[17]

Avoiding a conflict of interest

- Section 20 of the Determination requires registered tax practitioners, where appropriate and possible, to avoid any material conflict of interest that they have identified in connection with an activity undertaken, or due to be undertaken, for an Australian government agency, except to the extent that the government agency has expressly provided otherwise.

- A number of mechanisms may be adopted to avoid a conflict of interest, such as those described at paragraphs 56 and 57 above. Registered tax practitioners should exercise their professional judgement to determine the most appropriate method to avoid a conflict of interest.

- In some cases, regardless of arrangements put in place, conflicts will be unmanageable and the only way to adequately manage the conflict will be to avoid it altogether. This will generally require the registered tax practitioner to decline the engagement. Otherwise, the continued engagement by the government agency of the practitioner will be at the discretion of the agency having regard to the nature of the conflict and any steps taken by the practitioner to manage or mitigate the conflict.

Continued engagement at the discretion of the Australian government agency

- Once a conflict of interest is disclosed to the Australian government agency, the continued engagement of the registered tax practitioner will be at the discretion of the Australian government agency.

- An assessment of whether to continue with the engagement may consider factors such as:

- the nature and extent of the conflict of interest

- steps taken by the registered tax practitioner to manage the conflict of interest

- any mitigating actions taken by the registered tax practitioner

- the sensitive nature of the activities undertaken for the Australian government agency

- the damage, financial or otherwise, that may result should the engagement continue

- whether there are opportunities to obtain information and/or services relevant to the activities undertaken by the Australian government agency from an entity that does not have a conflict

- the extent to which the risks arising from the conflict can be appropriately managed

- whether the risk of accepting the conflict outweighs the risk of not obtaining the necessary information and/or services relevant to the activities undertaken by the Australian government agency.

- The discretion recognises that there may be circumstances where the only way the government agency can obtain relevant and necessary expertise is from a registered tax practitioner that has a conflict of interest.

- In these circumstances, the government agency may provide express consent to accept a conflict of interest. Where express consent is provided, the conflict of interest must be managed in a way that is consistent with that express consent. It must also be managed in a way that is consistent with the obligation in section 25 of the Determination

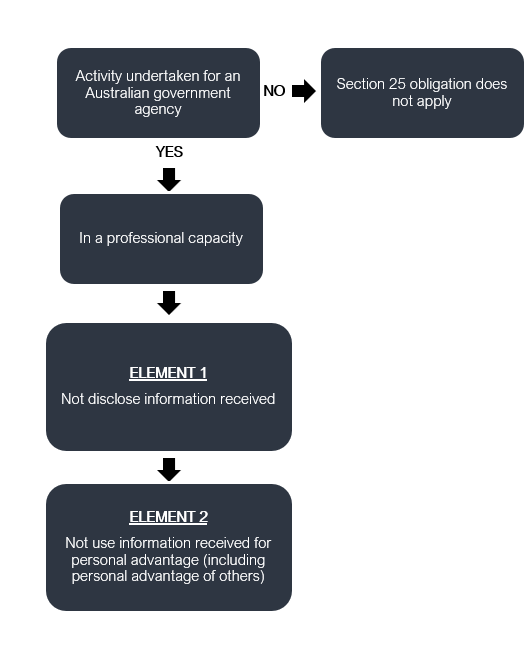

What is the obligation under section 25?

- Section 25 of the Determination gives rise to 2 obligations in relation to maintaining confidentiality in dealings with Australian government agencies:

- subject to some exceptions (see paragraphs 84 to 96), not disclose any information received, directly or indirectly, from an Australian government agency in connection with any activities undertaken for that agency in a registered tax practitioner's professional capacity

- subject to some exceptions (see paragraphs 106 to 110), not use any information received, directly or indirectly, from an Australian government agency in connection with any activities undertaken for that agency in a registered tax practitioner's professional capacity, for their personal advantage, or for the advantage of an associate employee, employer or client of the registered tax practitioner.

- The obligation is intended to protect against the unauthorised disclosure and improper use by registered tax practitioners of information they obtain in relation to activities they undertake for an Australian government agency.

Activities undertaken for an Australian government agency in your professional capacity

- Like the obligation under section 20 of the Determination, the obligations under section 25 apply to activities undertaken by a registered tax practitioner for an Australian government agency in the practitioner’s professional capacity, whether paid or otherwise.

- For more information in relation to activities undertaken for an Australian government agency in a tax practitioner’s professional capacity, see paragraphs 15 to 21 above.

Obligation to not disclose information

- Subsection 25(1) of the Determination prohibits registered tax practitioners from disclosing information they receive (directly or indirectly) from an Australian government agency in connection with activities they undertake for the government agency in their professional capacity, unless there is a legal duty to do so or to the extent that the following apply:

- it is reasonable to conclude that the information received from the Australian government agency was authorised by that agency for further disclosure, and

- any further disclosure of the information was done consistently with the agency’s authorisation.

- For example, these requirements may limit authorised disclosure of government information to certain tax practitioners or individuals within an entity, rather than the entity as a whole.[18]

- The obligation is not intended to apply to information released by the government agency to the general public (either published on a publicly available government website or through the media), nor does it extend to activities or interactions of a personal nature.[19]

- The key concepts of this obligation are explained further below.

What is ‘information’?

- ‘Information’ refers to the acquiring or deriving of knowledge obtained in connection with activities undertaken for an Australian government agency by a registered tax practitioner in their professional capacity. This information could be acquired either directly or indirectly from the government agency or other sources.

- Examples of information that may be received from an Australian government agency include the following:

- proposed government reform, including potential legislative changes

- information about procurement processes, including tender or pricing information, an agency’s project budget, pre-tender estimates, or evaluation methodologies

- personal information about entities

- cabinet in-confidence documents or market sensitive information.

What is a third party?

- The obligation under section 25 will apply to any disclosure to a ‘third party’.

- A third party means any entity other than the registered tax practitioner and the government agency.

- In relation to a registered tax practitioner that outsources a component of the tax agent services to another entity (for example, another registered tax practitioner, a legal practitioner, a contractor, or an overseas or offshore entity), the third party would include that other entity.

- Further, a third party may also include entities that maintain offsite data storage systems (including unencrypted ‘cloud storage’).

- In the case of a tax agent with a tax (financial) advice services condition that is an authorised representative of an Australian financial services (AFS) licensee, a third party includes the AFS licensee, and vice versa.

- Subject to the relevant contractual arrangements, a third party may also include other AFS licensees, authorised representatives, para-planners, product providers and advisers, insurance brokers, and technical teams and advisers.

In what circumstances can a registered tax practitioner disclose information to a third party?

- A registered tax practitioner may only disclose information received in connection with activities undertaken for an Australian government agency if:

- it is reasonable to conclude that the further disclosure of the information received from the Australian government agency was authorised by that agency and the further disclosure was done consistently with the agency’s authorisation, or

- there is a legal duty to do so.

- This ensures that government agencies can establish the limits on with who and how the information may be shared.

- Subsection 25(1) of the Determination complements section 20 in circumstances where the disclosure is authorised to certain registered tax practitioners with a need to know the information, and not authorised to be disclosed to people who may have a material conflict of interest. For example, these requirements may limit authorised disclosure of government information to certain registered tax practitioners or individuals within an entity, rather than the entirety of an entity.[20]

Reasonable to conclude further disclosure of information was authorised by Australian government agency

- Where it is reasonable to conclude that the information received from the Australian government agency was authorised by that agency for further disclosure, and the further disclosure of the information was done consistently with that authorisation, the tax practitioner will not contravene subsection 25(1) of the Determination.

- Applying this standard, if a reasonable person, possessing the required knowledge, skill and experience of a registered tax practitioner, objectively determined, would conclude that the further disclosure of the information was authorised by the government agency, this will be sufficient. It is not necessary to determine the question with any certainty. For example, it would be reasonable to conclude that further disclosure of the information was authorised by the Australian government agency in the following circumstances:

- the further disclosure was expressly authorised by the government agency, either in writing or otherwise (for example, the formal engagement letter included a clause authorising the disclosure of information), or

- authorisation of the further disclosure was implied by the government agency, either in writing or otherwise.

- Other relevant factors in determining whether it is reasonable to conclude that further disclosure of the information was authorised by the Australian government agency may include the following:

- comments made by the government agency when providing the information to the registered tax practitioner, or

- the availability of the information provided to the registered tax practitioner from other sources.

- Ultimately, the registered tax practitioner should use their professional judgment to assess whether the further disclosure of the information by the registered tax practitioner was authorised, having regard to the circumstances.

- There is no requirement that the information be marked as confidential or identified as for limited distribution although this may be a relevant factor in interpreting whether it is reasonable to conclude that further disclosure of the information is authorised by the government agency.

- Where a registered tax practitioner intends to disclose, to a third party, information received from an Australian government agency in connection with any activities undertaken for the government agency, the TPB recommends that the registered tax practitioner should, prior to any disclosure, clearly inform the government agency that there will be such a disclosure and obtain the government agency’s permission. This permission may be by way of a signed letter outlining the information that is to be disclosed and to whom the information is to be disclosed to, signed consent or other communication with the government agency. In all cases, the relevant communication should outline the disclosures to be made, as well as information about the entity/entities that will have access to the information disclosed.

- While there is no set formula or methodology used to obtain the Australian government agency’s permission, the TPB suggests that registered tax practitioners be clear in explaining to the government agency where information may be disclosed (including, among other things, where a component of the activity or add-on activity will be completed). For example, to avoid any likelihood of a registered tax practitioner’s practices being seen as misleading, the TPB suggests that tax practitioners do not imply or state that all activities undertaken for the government agency will be completed in Australia, if that is not the case.

- In relation to outsourcing arrangements and cloud storage arrangements, the TASA does not specifically prohibit these activities. However, tax practitioners must consider their obligations under section 25 of the Determination in relation to these arrangements to ensure confidentiality of information received from an Australian government agency in connection with any activities undertaken for the government agency, including appropriate disclosure in regard to where data is being sent and stored.[21]

- While not binding on all registered tax practitioners, further useful guidance on what steps a registered tax practitioner may take when providing or utilising outsourced services may be found in specific APESB guidance.[22] It is also noted that TPB accredited recognised professional associations may be able to assist in providing practical guidance, while recognising that there is not a default one-size-fits-all template and that arrangements will need to be mindful of the particular circumstances.[23]

Legal duty to do so

- A registered tax practitioner may disclose information in connection with activities they undertake for an Australian government agency to a third party without the government agency’s agreement if the tax practitioner has a legal duty to disclose the information.

- Examples of circumstances where a registered tax practitioner may have a legal duty to disclose such information to a third party include:

- providing information requested by the TPB in undertaking enquiries about the registered tax practitioner’s conduct, including information requested under a notice issued pursuant to section 60-100 of the TASA

- providing information to the TPB under the breach reporting obligations in sections 30-35 and 30-40 of the TASA

- providing information to a court or tribunal pursuant to a direction, order, or other court process to provide that information

- providing information to AUSTRAC in accordance with reporting obligations under the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Act 2006 (AML/CTF Act)[24]

- providing information or documents to the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) under a notice pursuant to section 353-10 in Schedule 1 to the Taxation Administration Act 1953 concerning taxation laws

- providing information to an AFS licensee pursuant to section 912G of the Corporations Act, as inserted by ASIC Class Order [CO 14/923] Record-keeping obligations for Australian financial services licensees when giving personal advice, which requires an authorised representative of an AFS licensee to give records to the AFS licensee if requested by the AFS licensee, provided the request is made:

- in connection with the obligations imposed on the AFS licensee under Chapter 7 of the Corporations Act; and

- within 7 years after the day on which the personal advice was provided to the client.

- The TASA, including section 25 of the Determination, does not affect the law relating to legal professional privilege (LPP).[25] LPP protects confidential communications between a lawyer and their client from compulsory production. At times, a registered tax practitioner may be in possession of client documents or information that may be subject to LPP, such as legal advice about a client’s tax affairs which has been provided on a confidential basis. Before disclosing client documents or information to a third party, a tax practitioner should consider whether any of the documents may be subject to LPP. Where a registered tax practitioner considers that LPP may apply, they should seek legal advice as to the application of LPP. Accordingly, in the practical examples given in paragraphs 129 and 130 below, a tax practitioner would need to consider any additional LPP obligations.

- If a registered tax practitioner is concerned as to whether there is a legal duty to disclose information received in connection with any activities they undertake with the Australian government agency to a third party, the tax practitioner should consider seeking independent legal advice.

Inadvertent disclosure

- Registered tax practitioners also need to ensure they have appropriate arrangements to prevent inadvertent disclosure.[26] In this regard, the following are some examples of where tax practitioners need to be particularly mindful of their obligations:

- leaving information in unsecured locations which may be accessed by third parties

- disposing (such as trading in or selling to a second-hand market) of IT equipment or mobile devices that contain / store data that may be accessible by third parties

- the use of shredding and data disposal services

- the use of external service providers which may include, for example, IT consultants, virtual assistants, and cleaners

- the use of virtual meetings to discuss information when third parties may be in attendance

- the use of public Wi-Fi or unsecure network when providing services for a government agency

- the use of unencrypted cloud storage.

Other considerations – Privacy

- In addition to a tax practitioner’s obligations under subsection 25(1) of the Determination, the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) (Privacy Act) sets out a number of Australian Privacy Principles (APP) which govern the use of, storage and disclosure of personal information and other conduct by organisations.[27] Some of these privacy principles may be relevant to the obligation under subsection 25(1) of the Determination. For example, APP6 outlines the circumstances in which an APP entity[28] may use or disclose personal information that it holds. Further, APP11 states that an APP entity must take reasonable steps to protect personal information it holds from misuse, interference and loss, and from unauthorised access, modification or disclosure.

- Registered tax practitioners should seek their own advice about whether the provisions of the Privacy Act apply to them. Information about obligations under the Privacy Act is accessible from the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner’s website at www.oaic.gov.au.

Obligation to not use information for personal advantage

- Subsection 25(2) of the Determination prohibits registered tax practitioners from using information they receive (directly or indirectly) from an Australian government agency in connection with activities they undertake for the government agency in a professional capacity, in a way that may provide a personal advantage, except to the extent the following apply:

- it is reasonable to conclude that the information received from the Australian government agency was authorised by that agency to be used in a way that may provide for such a personal advantage, and

- any further use of the information was done consistently with the agency’s authorisation.

What is a personal advantage?

- ‘Personal advantage’ is not defined in the TASA.

- The TPB is of the view that a personal advantage refers to interests that involve potential gain, financial or otherwise, for the registered tax practitioner. It may also be direct or indirect.

- It is not necessary that the use of the information was likely or guaranteed to result in a personal advantage.[29] The mere possibility that the information has the potential to result in a personal advantage is enough to trigger the obligation.

- The obligation imposes a strict restriction on registered tax practitioners to ensure that no personal advantage is taken from using information obtained from government agencies in relation to activities undertaken for that agency, except where it is reasonable to conclude that the agency authorised this use.[30]

- Subsection 25(2) of the Determination extends the obligation further to include the use of that information for the personal advantage of an associate, employee, employer, or client. This ensures that any potential indirect benefits do not flow to the registered tax practitioner through the unauthorised disclosure of such information for the personal advantage of others.

In what circumstances can a registered tax practitioner use information for personal advantage?

- A registered tax practitioner may only use information received in connection with activities undertaken for an Australian government agency for the tax practitioner’s personal advantage, or the advantage of an associate, employee, employer (which may include the recognised professional association of the registered tax practitioner), or client, if:

- it is reasonable to conclude that the use of the information received from the government agency was authorised by that agency to be used in a way that may provide such a personal advantage, and

- any further use of the information was done consistently with the agency’s authorisation.

- A registered tax practitioner must satisfy both parts of paragraph 106 above to be able to use the information for their personal advantage, or the advantage of an associate, employee, employer, or client.

- Applying this standard, if a reasonable person, possessing the required knowledge, skill and experience of a registered tax practitioner, objectively determined, would conclude that the use of the information for such purpose was authorised by the Australian government agency, this will be sufficient. It is not necessary to determine the question with any certainty, although it is recommended that tax practitioners seek consent if in any doubt.

- Ultimately, the tax practitioner should use their professional judgment to assess whether the use of the information for the tax practitioner’s personal advantage, or the advantage of others, was authorised, having regard to the circumstances.

- In determining whether it is reasonable to conclude that the Australian government agency authorised the use of the information for the personal advantage of the registered tax practitioner, or for the advantage of an associate, employee, employer or client, the following factors may be relevant:

- the use of the information for the personal advantage of the registered tax practitioner (or others) was expressly authorised by the government agency, either in writing or otherwise (for example, the formal engagement letter included a clause authorising the information to be used in such a manner), or

- the use of the information for the personal advantage of the registered tax practitioner (or others) was implied by the government agency, either in writing or otherwise.

Consequences for failing to comply under the TASA

- A breach of any of the requirements in the Determination, including sections 20 and 25, will constitute a breach of subsection 30-10(17) of Code in the TASA.

- Registered tax practitioners will be required to notify:

- the TPB if they have reasonable grounds to believe that they have breached the Code and that breach is significant, and

- the TPB and the relevant recognised professional association (if applicable), if they have reasonable grounds to believe that another registered tax practitioner has breached the Code and that breach is significant.[31]

- In relation to the reporting of a significant breach relating to another registered tax practitioner’s conduct, particularly in the context of disclosing the details of another person’s or entity’s conflict of interest in undertaking the same or different activity for an Australian government agency, the TPB will assess the information provided and make further enquiries (as appropriate) to ensure the reporting of a significant breach is not frivolous, vexatious or malicious.

- The TPB may take action against the notifying registered tax practitioner if the TPB considers that a breach report is frivolous, vexatious or malicious, for example, if the claim involves the making of a false or misleading statement. Such situations may raise issues about the notifying registered tax practitioner’s compliance with other requirements of the TASA, including:

- the fit and proper person requirement, which registered tax practitioners must meet to maintain their registration, and

- other Code items, including the requirement to act with honesty and integrity (Code item 2), which may lead to the imposition of administrative sanctions.

- If the TPB finds that a registered tax practitioner has breached the Code, the TPB may impose one or more of the following sanctions:

- a written caution

- an order requiring the registered tax practitioner to do something specified in the order

- suspension of the registered tax practitioner’s registration

- termination of the registered tax practitioner’s registration (including a period within which the terminated tax practitioner may not re-apply for registration).

- In addition, the same conduct which may constitute a failure to comply with sections 20 and 25 of the Determination could also constitute a breach of another Code obligation (such as the obligation to act with honesty and integrity).

- Further, if the TPB finds that a registered tax practitioner has failed to meet an ongoing tax practitioner registration requirement (for example, by no longer being a fit and proper person), the TPB may terminate the tax practitioner’s registration.

- Ultimately, determining whether a registered tax practitioner has contravened the TASA will be a question of fact. This means that each situation will need to be considered on a case-by-case basis having regard to the particular facts and circumstances of that case.

Comparison with the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) for tax agents with a tax (financial) advice services condition

- The TPB recognises that the obligations of some Australian financial services (AFS) licensees and their representatives under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act) are similar to some obligations under the TASA.

- Ultimately, while compliance with relevant Corporations Act and Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) requirements will be a relevant factor, it is not conclusive in relation to whether obligations under sections 20 and 25 of the Determination have been satisfied.

- In particular, it is noted that paragraph 912A(1)(aa) of the Corporations Act provides that a financial services licensee must:

- have in place adequate arrangements for the management of conflicts of interest that may arise wholly, or partially, in relation to activities undertaken by the licensee or a representative of the licensee in the provision of financial services as part of the financial services business of the licensee or the representative.

- Further, Standard 3 of the Financial Planners and Advisers Code of Ethics 2019, requires that all relevant providers must not advise, refer or act in any other manner where you have a conflict of interest or duty.

- In addition, subsection 961B(1) of the Corporations Act requires that, in the provision of personal advice to a person as a retail client, the provider must act in the best interests of the client in relation to the advice (best interests duty).

- Further, the best interests duty is supplemented by subsection 961J(1) of the Corporations Act which requires that if the provider knows, or reasonably ought to know, that there is a conflict between the interests of the client and the interests of the provider or their related parties (such as licensees, authorised representatives and associates), the provider must give priority to the client’s interests when giving the advice (conflicts priority rule).[32]

- The primary distinction between the obligations under section 20 of the Determination as compared with the best interests duty / conflicts priority rule is that section 20 of the Determination requires that the registered tax practitioner identify and disclose certain matters in relation to material conflicts of interest, whether real or apparent. In comparison, the best interests duty / conflicts priority rule under the Corporations Act is more narrowly focused on how to deal with an actual conflict of interest.

- Further, the best interests duty / conflicts priority rule under the Corporations Act merely requires that the client’s interests be prioritised in the event of an actual conflict, whereas section 20 of the Determination is broader and requires that arrangements must be in place in relation to material conflicts of interest, whether real or apparent, and if possible and appropriate, reasonable steps are to be taken to avoid the conflict of interest.[33]

- Another distinction between the obligation under section 20 of the Determination, and the best interests duty / conflicts priority rule is that section 20 applies broadly to any activities that a registered tax practitioner undertakes for an Australian government agency in their professional capacity. In comparison, the best interests duty / conflicts priority rule under the Corporations Act only applies to those providing personal advice to retail clients.

- It is noted that if an AFS licensee or an authorised representative of an AFS licensee fails to comply with the Corporations Act (including the best interests duty), they may be liable for:

Case studies – section 20 of the Determination

- These case studies provide general guidance only. In all cases, consideration will need to be given to the specific facts and circumstances.

Case study 1 - Conflict of interest not disclosed to Australian government agency

Situation

Ann is a registered tax agent and a tax partner at a large tax consulting firm. Ann is asked to participate in a confidential consultation led by an Australian government agency in relation to proposed draft legislation concerning new integrity measures that relate to the tax consolidation rules. If implemented, these rules would apply to clients of the large consulting firm, including Ann’s own clients.

Upon receiving the confidential consultation papers, Ann identifies that if the new integrity measures took effect, they would adversely impact the tax affairs of some of her clients. Ann identified that her duty to her clients could be perceived as a material conflict of interest, noting that in the circumstances, there was a potential opportunity for her to financially benefit from her knowledge of those proposed new integrity measures by offering advice to those clients who would be impacted (and potentially new clients) on how they could restructure their affairs before the government agency published the draft legislation. She does not document this conflict of interest, nor disclose it to the government agency. She also takes no steps to manage, mitigate or avoid the conflict of interest, despite the existence of reasonable steps she could have taken to document the conflict of interest, or manage, mitigate, or avoid it.

Breach of section 20 of the Determination

Ann has breached her obligation under section 20 of the Determination.

Ann has identified a material conflict of interest in connection with the activities she is undertaking for the government agency and the duty she owes to the agency to maintain confidentiality. She has failed to document and disclose this conflict to the government agency. In addition, it cannot reasonably be concluded that the government agency expressly provided that Ann could continue to participate in the confidential consultation.

In breaching section 20 of the Determination, Ann is in breach of subsection 30-10(17) of the TASA for failing to document and disclose the conflict of interest to the government agency. Further, if Ann used the confidential information to financially benefit from her knowledge of the proposed new integrity measures, the TPB may also find that Ann is in breach of subsections 30-10(1) of the TASA (failing to act with honesty and integrity) and is no longer a fit and proper person to be registered as a tax practitioner.

Case study 2 - Agency authorises continued engagement following disclosure of conflict of interest

Situation

Max is a registered tax agent and a tax partner at a large accounting firm. Max’s clients include several large corporations. Max is an expert in company tax law and is often engaged by his clients to advise on how they may lawfully arrange their tax affairs to reduce tax that they may otherwise be liable for. He also regularly lectures on this topic at several Australian universities and has published numerous peer-reviewed articles on the matter.

Due to his expertise in this field, Max is engaged by The Treasury to assist in the design of several company tax law reform measures.

Max immediately documents and discloses the conflict of interest to The Treasury, advising of the nature and extent of the conflict of interest, and provides a broad overview of the nature of the advice and services he provides to his clients. He discloses to The Treasury that his clients include several large corporations that may be adversely impacted by the proposed reform measures. Further, Max provides The Treasury with an overview of how he intends to manage and mitigate the conflict should the engagement continue, noting that his only option to avoid the conflict is to decline the engagement. He informs The Treasury that he has taken the following steps to manage and mitigate the conflict of interest:

- recorded the conflict of interest on the firm’s conflict register

- reviewed the firm’s internal governance policies in relation to conflicts of interest, including the provisions concerning consequences for failing to comply with the procedures, to ensure compliance with those internal policies, and

- ensured that access to information concerning the reform measures is restricted to those who are also assisting in the design of the reform measures (assuming others are engaged to assist in the design of these reforms).

Following the disclosure of the conflict of interest, The Treasury decides to continue with the engagement, noting the mitigating actions taken by Max and Max’s expertise in company tax law. The Treasury provides Max with its express written consent to continue with the engagement, providing Max implements appropriate mitigation measures and those measures continue to be consistent with the express consent throughout the engagement.

Conflict of interest

Max has met his obligation in section 20 of the Determination.

Max has appropriately identified, documented, and disclosed the material conflict of interest to The Treasury. He has also provided The Treasury with details of how he intends to manage and mitigate the conflict of interest, noting that the conflict of interest may only be appropriately avoided if he declined the engagement with the Treasury.

Case Study 3 - Conflicts of interest considered not material

Situation

John is a registered tax practitioner and expert on the Australian superannuation laws. John is engaged by an Australian government agency to provide advice in relation to a proposed superannuation reform package aimed at improving the fairness, sustainability, flexibility and integrity of the superannuation system. The proposed reforms are intended to apply to all superannuation funds.

John is a passive member of 123 Super Fund. Although John identifies that there is a conflict of interest, given he is a member of a superfund that will be impacted by the proposed reform package, he assesses this conflict as one that is not material in the circumstances. Nonetheless, John documents and discloses the conflict to the government agency.

Conflict of interest

John has met his obligation under section 20 of the Determination.

Although John has identified that the conflict of interest in connection with the activities he is undertaking for the government agency is not material, he has nonetheless documented and disclosed the conflict to the government agency.

Even if John had not disclosed the conflict to the government agency, he would not have breached section 20 of the Determination given the conflict was not material.

Case studies - Section 25 of the Determination

- These case studies provide general guidance only. In all cases, consideration will need to be given to the specific facts and circumstances.

Case study 4 – Agency authorises disclosure of information to third party practitioner

Situation

Thomas is a registered tax agent and a tax partner at a mid-sized accounting firm. Thomas is invited to a set of confidential round table discussions led by The Treasury in relation to a proposed increase to tax rates that would largely impact high-wealth individuals. The proposed increase in the tax rates would impact a large portion of the firm’s client base.

The invitation to participate in the round table discussions sets out the proposed terms of the engagement, including to whom information received in connection with any activities that Thomas is to undertake for The Treasury may be disclosed. The terms make it clear that a core group of expertise within the firm could be established to participate in the round table discussions and other dialogue in relation to the proposed tax-rate hike, but that the information could not be disseminated further.

Thomas asks 2 of the firm’s partners to participate in the engagement and this is communicated to, and authorised by, The Treasury. Throughout the engagement, Thomas discloses information to the 2 partners and no further disclosure of the information occurs.

Is there a breach of subsection 25(1) of the Determination?

Thomas has not breached subsection 25(1) of the Determination.

It is reasonable to conclude that the information received in connection with the activities Thomas has undertaken for The Treasury was authorised by the department to be disclosed to the core group, noting in particular the proposed terms of engagement. In addition, Thomas and the core group did not disclose that information further.

Case study 5 – Agency authorises disclosure of information to third party practitioner, but disclosure is inconsistent with that authorisation

Situation

In Case Study 4, Thomas has been authorised to disclose certain information in relation to activities he is undertaking for The Treasury to a core group to be established within his firm. The authorisation provided to Thomas clearly states how that information is to be communicated to this core group, what information can be disseminated, what information is to remain strictly confidential and not for further dissemination to that core group, and for what purpose that information is to be used. Importantly, the authorisation clearly stipulates that any information shared with that core group is to be provided through email only (with a carbon copy (cc) to The Treasury) and not to be provided in printed form.

Thomas asked 2 of the firm’s partners to participate in the engagement. Throughout the engagement, Thomas discloses information to the 2 partners. On several occasions, Thomas prints emails from The Treasury in relation to the confidential round table discussions, including confidential meeting papers, and provides those to the 2 partners.

Is there a breach of subsection 25(1) of the Determination?

Thomas has breached subsection 25(1) of the Determination.

It is not reasonable to conclude that the information received in connection with the activities Thomas has undertaken for The Treasury was authorised by the department to be disclosed to the core group in the manner in which it was disclosed, noting that the authorisation provided to Thomas by The Treasury clearly stipulated that information shared with the core group was to be shared through email only (with a cc to The Treasury).

In breaching subsection 25(1) of the Determination, Thomas is in breach of subsection 30-10(17) of the Code in the TASA for making disclosures of the confidential information in a manner that was not consistent with The Treasury’s authorisation.

Case study 6 – Agency does not authorise disclosure of information to third party practitioner

Situation

Isabella is a registered tax agent and a tax partner at a large tax consulting firm. Isabella is asked to participate in a confidential consultation by The Treasury in relation to new measures aimed at improving the tax laws. This confidential consultation included new rules to stop multinationals avoiding tax by shifting profits from Australia to tax havens overseas.

The consultation papers distributed to Isabella were marked “under embargo”. In addition, Isabella was asked to sign a confidentiality agreement as part of her formal engagement. The confidentiality agreement signed by her clearly stipulated that any information received, directly or indirectly, in connection with any activities undertaken for The Treasury in relation to these new measures, is not for further dissemination and that any further disclosure would require the prior authorisation of the government agency.

Throughout the engagement, Isabella made unauthorised disclosures of the confidential law reform to partners and staff within the consulting firm.

Is there a breach of subsection 25(1) of the Determination?

Isabella has breached her obligation under subsection 25(1) of the Determination.

Isabella has disclosed information she received from The Treasury in connection with activities she undertook for the department in her professional capacity. Further, it is not reasonable to conclude in the circumstances that the information received by Isabella was authorised by The Treasury for further disclosure.

In breaching subsection 25(1) of the Determination, Isabella is in breach of subsection 30-10(17) of the Code in the TASA for making unauthorised disclosures of the confidential information. Depending on the circumstances, the TPB may also find that Isabella is in breach of subsections 30-10(1) of the TASA (failing to act with honesty and integrity) and/or that she is no longer a fit and proper person to be registered as a tax practitioner.

Case study 7 – Agency does not authorise use of information for personal advantage

Situation

In Case study 6, during her engagement in the confidential consultation, Isabella became aware that clients of the firm would be impacted by the proposed new measures. Isabella chose to disclose the information received from The Treasury in connection with the activities she was undertaking for the department in her professional capacity for her personal advantage, noting that she stood to gain financially by disclosing the information to the partners of the firm whose clients would be impacted. Similarly, the partners, and others within the firm to whom the confidential information was also disclosed, would gain personally from the unauthorised disclosure, noting the financial benefit that would be gained by informing impacted clients prior to The Treasury publishing the draft legislation.

Is there a breach of subsection 25(2) of the Determination?

Isabella has breached her obligation under subsection 25(2) of the Determination.

In addition to the unauthorised disclosure of confidential information, Isabella has also used this information she received from The Treasury in connection with activities she undertook for The Treasury in her professional capacity for her personal advantage, and the personal advantage of others within the consulting firm. Further, it is not reasonable to conclude in the circumstances that the use of the information received by Isabella was authorised by The Treasury to be used in a way that may provide for such a personal advantage.

In breaching subsection 25(2) of the Determination, Isabella is in breach of subsection 30-10(17) of the TASA, for making unauthorised disclosures of the confidential information for her personal advantage. In the circumstances, it is possible that the TPB may also find that Isabella is in breach of subsections 30-10(1) of the Code in the TASA (failing to act with honesty and integrity) and/or that she is no longer a fit and proper person to be registered as a tax practitioner.

Case study 8 – Agency does not authorise use of information for personal advantage

Situation

Adam is a registered tax practitioner and is employed by a recognised professional association as head of its tax training program. This program is designed to equip graduates with specialist tax knowledge, and upon completion of the program, a tax specialist certification. Adam has extensive experience over several decades in designing and delivering the curriculum of the program. His area of expertise is the taxation of trusts.

Due to Adam’s experience in developing tax training programs, particularly on the topic of taxation of trusts, Adam is engaged by The Treasury to assist in drafting a consultation paper on proposed reforms to the taxation of trust income.

Adam disclosed information in relation to the proposed reforms to the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the recognised professional association. He discussed his intention to commence work on developing a new training program that could be marketed and offered as soon as a public announcement was made on the proposed reforms. Both Adam and the recognised professional association stood to gain financially as a result of Adam’s disclosure of the confidential information, noting that the recognised professional association would gain a competitive advantage by commencing work on and releasing the tax training program into the market before other competitors.

Is there a breach of subsection 25(2) of the Determination?

Adam has breached his obligation under subsection 25(2) of the Determination.

In addition to the unauthorised disclosure of confidential information, Adam has also used this information he received from The Treasury in connection with activities he undertook for The Treasury in his professional capacity for his personal advantage, and the personal advantage of his employer (the recognised professional association). Further, it is not reasonable to conclude in the circumstances that the use of the information received by Adam was authorised by The Treasury to be used in a way that may provide for such a personal advantage.

In breaching subsection 25(2) of the Determination, Adam is in breach of subsection 30-10(17) of the TASA, for making unauthorised disclosures of the confidential information for his personal advantage, and the personal advantage of his employer. In the circumstances, it is possible that the TPB may also find that Adam is in breach of subsections 30-10(1) of the Code in the TASA (failing to act with honesty and integrity) and/or that he is no longer a fit and proper person to be registered as a tax practitioner.

Further information

Outlined below is a listing of reference material that may provide further guidance in relation to issues to consider in relation to managing conflicts of interest and maintaining confidentiality.

Reference materials - Information product

TPB(I) 19/2014 Code of Professional Conduct – Managing conflicts of interest Purpose of document Assists registered tax practitioners to understand their obligations under subsection 30-10(5) of the TASA (Code of Professional Conduct (Code) item 5). TPB(I) 21/2014 Code of Professional Conduct – Confidentiality of client information Purpose of document Assists registered tax practitioners to understand their obligations under subsection 30-10(6) of the TASA (Code of Professional Conduct (Code) item 6). TPB(I) D53/2024 Breach reporting under the Tax Agent Services Act 2009 Purpose of document Assists registered tax practitioners to understand the breach reporting obligations under sections 30-35 and 30-40 of the TASA, which apply from 1 July 2024. Reference materials - Information product

Purpose of document TPB(I) 19/2014 Code of Professional Conduct – Managing conflicts of interest Assists registered tax practitioners to understand their obligations under subsection 30-10(5) of the TASA (Code of Professional Conduct (Code) item 5). TPB(I) 21/2014 Code of Professional Conduct – Confidentiality of client information Assists registered tax practitioners to understand their obligations under subsection 30-10(6) of the TASA (Code of Professional Conduct (Code) item 6). TPB(I) D53/2024 Breach reporting under the Tax Agent Services Act 2009 Assists registered tax practitioners to understand the breach reporting obligations under sections 30-35 and 30-40 of the TASA, which apply from 1 July 2024.

Consultation questions

The TPB welcomes submissions addressing all aspects of this draft TPB(I). The following consultations questions may assist you in providing feedback:

Consultation questions Q1 Do you have any general comments regarding the guidance on the obligation under section 20 of the Determination? Q2 Are the factors outlined at paragraph 39 in relation to whether a registered tax practitioner has taken reasonable steps to identify and document any material conflict of interest adequate and appropriate? If no, please provide further detail including any additional factors that should be included. Q3 Are the steps and techniques outlined at paragraphs 56 and 57 in relation to reasonable steps to manage, mitigate, and where appropriate and possible, avoid, any material conflict of interest adequate and appropriate? If no, please provide further detail including any additional steps or techniques that should be included. Q4 Do you have any general comments regarding the guidance on the obligation under section 25 of the Determination? Q5 Are there additional case study scenarios that would assist registered tax practitioners in understanding how the obligations under section 20 and 25 of the Determination apply practically? If so, what types of scenarios should be addressed?

References

[1] The TPB administers a system for the registration of tax agents and BAS agents (known collectively as ‘tax practitioners’) under the Tax Agent Services Act 2009 (TASA).

[2] The TPB has also published specific information regarding the obligations of registered tax practitioners under subsection 30-10(5) of the TASA, including TPB(I) 19/2014 Code of Professional Conduct – Managing conflicts of interest.

[3] The TPB also published specific information regarding the obligations of registered tax practitioners under subsection 30-10(6) of the TASA, including TPB(I) 21/2014 Code of Professional Conduct – Confidentiality of client information.

[4] The provisions of the Code are contained in section 30-10 of the TASA. The TPB has also published an explanatory paper that sets out its views on the application of the Code, including Code obligations 5 and 6. Refer to TPB Explanatory paper TPB(EP) 01/2010 Code of Professional Conduct.

[5] For further information, see TPB Explanatory paper TPB (EP) 02/2010 Fit and proper person.

[6] It is noted that as at the date of publication of this draft TPB(I), the government completed consultation on a draft Commonwealth Supplier Code of Conduct which is aimed at further strengthening integrity and ethical conduct in government operations and those of its suppliers. This Code is expected to come into effect in mid-2024.

[7] See APES 110 Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants, sections 100, 220 and 310 on the Accounting Professional & Ethical Standards Board website at www.apesb.org.au

[8] For more information in relation to the definition of a tax agent service, see TPB Information Sheet TPB(I) 39/2023 What is a tax agent service?.

[9] For more information in relation to the definition of a BAS service, see TPB Information Sheet TPB(I) 38/2023 What is a BAS service?.